Heroic Architecture: writings on the wall

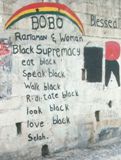

The most heroic moments in the process of transformation of a civilisation are the buildings that this process throws up. Why are such buildings heroic? Because they present their façade to the world as a hero would present his body to the enemy. Architecture in Kingston is often heroic in this way, used as a vehicle of ideology and protest: each home becomes a contract of allegiance, an icon of political, utopian or religious affiliation and desire. The bible, the writings of Marcus Garvey and other texts become instruments of public political alignment: quotations are painted over entrances; wall-paintings and graffiti regulate the metabolism of people going in and out.

A food stand at the side of the road will advertise its politics, its religion and, as an afterthought, its wares. One particularly favourite example did not survive long enough for me to find an opportunity photograph it. It was a very modest blue painted structure selling individual cigarettes and warm beer. On the front was written, in an evocative and economical patois: “Me vex dem kill Malcolm X”. Another hut had written on its door a simple “Don’t Mess with Me”. One of my favourites is: “White Mynority rule black majority”. Beside it is a picture of Castro and Beanie Man. When I asked the man why he had painted Castro he said that Castro was the only white man who ever told the black man the truth.

An informal architecture has arisen which attempts to rehearse the unifying philosophy of Bob Marley and becomes an architecture of fearless independence. One example of this architecture is a Rastafarian “museum”. Along one wall is a declaration of independence, over the entrance is implied a solution to the whole problem of Kingston which finds wide support: Divide the land fairly and let people get on with it. It is true that people who feel their land securely under their own feet become visible proof of the creative energy in Jamaica.

Portmore, for instance, a dormitory suburb of Kingston, was intended as a low-cost housing development of dreary starter units regimented into the pattern of maximum returns. The minute people started settling there, these concrete and cheerless boxes underwent a wonderful metamorphosis: the boxes became castles of an extraordinary vitality.

Jamaica is, perhaps forced by its poverty and by other social forces to be at odds with the struggle for the glittery and empty prizes of the West. It wants those prizes, but because it can’t afford them and is to some extent excluded from them, it can instead afford anger at their own plight and those who are seen as the cause of that plight. Anger is a creative force.

This other Jamaica appears at least truly independent, in that it is forced to make do with what it has got. This making do has its own rich and varied aesthetic. It has created a face to Jamaica, which, while it lasts, is erect and full. That Jamaica sees with its own eyes, with that I mean peculiarly Jamaican eyes. Does things in its own way and becomes its own, a respectable nation true to its motto.