Havana V

Diary, 26th October 1998:

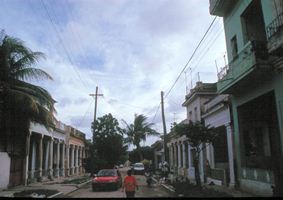

Hurricane Mitch has inundated Kingston. No wind but a lot of rain and flooding. I’worried about V. and the kids. We visited El Cerro, an area to the south of Vedado and Havana Centro. One of the small little gridded islands surrounded by three major roads that divide the gridded areas and make them crumple together and readjust themselves at their edges. The two corners of this island are chamfered by industry, a beautiful old brewery for instance. For the rest the grid is well grafted into the area, divided into two sections by a larger road and with a chaotic soft edge of wasteland to the west. Sal and I walked around and Sal’s Spanish helped us into numerous houses along the road or hidden within the Ciudadelas.

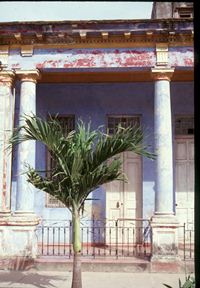

The area was developed during the middle of the last century with single-storey weekend villas for the wealthier people in Havana. These were arranged around generous courtyards and gardens and fronted the street with a generous veranda-like loggia. Other houses were added from about 1910 and a pattern started emerging. Double plots would have two houses with a single doorway between them. These houses would be generous and their rooms arranged en filade at right angles to the road: entrance hall, living room, 1st bedroom, bathroom, second bedroom, third bedroom, kitchen, patio. The patio would be connected directly through a narrow outdoor passage lined with windows to the various rooms, to the entrance hall. I have also seen the arrangement: entrance hall, living room, bedroom, bedroom, bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, patio. Some houses are occupied by a single family. Emerging from one of the houses we visited, I saw more people on the other side of the road than we had on our side. Our side of the road was very quiet. It appeared that this was so because the level of subdivision was higher on that side of the road. The interior of the house I had just emerged from was rather wonderful, high, slim doors all neatly in line. The hall was separated from the living room only by a set of twisted columns painted white, the walls were orange and the ceilings very high and consisted of rows of shallow brick vaults. The walls were hung sparsely with richly coloured, cheap tapestries in deep reds and an old oil painting dating from the forties of a lady dressed in a cap and striped dress. There were the obligatory pictures of Jesus as well as a long painting of a naked woman as Cabanel or Bouguereau would have painted her. The bedrooms were simply decorated with small plastic statuettes and passport photographs behind old glass covering the tops of the bedside cabinets. In the patio or yard at the end of the house, the lady’s husband was busy tending to his fighting cockerels. He showed us his prize cockerel, which had, apparently, killed 16 other cockerels. It made a lot of noise in the royal cage specially built for it. The cage was adorned with a portrait of the beast listing all the names of the cockerels it had vanquished. The other cockerels, and there were many, were housed in much more unassuming cages. The daughter of the house was a doctor. It was not clear what the man did other than raise cockerels. The mother, the owner of the house, was deeply sunk in the reveries of age. It is difficult to say what the ladies felt about the cockfighting.

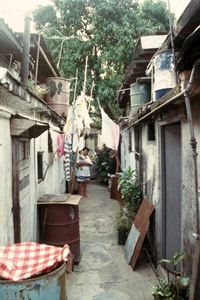

When we left we went to the opposite side of the street, where, as I said, more people seemed to gather. That was because of the ciudadela that was located there. A ciudadela is a small development within the combined courtyards of a set of two houses fronting the street and with a central doorway to the back between them. These are the result of developments in El Cerro that occurred when the economy started to decline and people began looked for other sources of income through their weekend villas. Well, at least that is the simple explanation, I am sure that the dynamic of ciudadela development has a more involved story. This ciudadela started with two wooden houses and a central entrance to the courtyard behind. From the central entrance a blind alley lead to a u-formed string of ten tiny houses facing a blank wall. The older wooden houses were originally as high as the villa we had just left, but had since been divided into two storeys. The mezzanine storey projected beyond the wooden façade with concrete balconies reaching right up to the building line, a space usually reserved for a spacious and elegantly tall veranda. The people complained about the tiny “solares” or houses. These consisted of a tiny downstairs living, dining room area, a closet kitchen and a bedroom upstairs. Two or three mattresses lying on the ground would sleep a whole family of seven. I was invited into a blind lady’s bedroom. She was old and very fragile. She began to talk to me of her stomach operation and about her blindness. The room was made of wood. There was nothing on the walls, I do not know how she had furnished the room of her own mind, but this room was a blind woman’s room, there was nothing but the deep pattern of peeling paint. Her bed was so irregular in its topography, looking more like an indifferently made model of a hilly landscape. She was permanently dressed in a night-gown and, as she was talking to me, now with words and rhythms well beyond what I could understand, she started crying. We left. Sometimes things that are small are big.

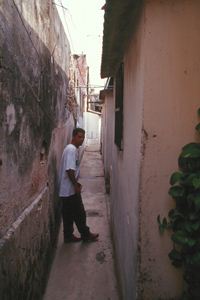

Further on we were invited into the home of a teacher of electronics. His old house, lining the street and the locus of a permanent game of dominoes, had collapsed. All that remained were the beautifully coloured walls. Behind the collapsed house were a patio and a modern concrete house. The patio was divided into two sections. One was a garden with banana trees, the other a gymnasium with all sorts ancient and improvised weight-lifting machines reduced to a rusty bare minimum. One of the ciudadela’s we entered was dominated by the presence of a young man with heavy eyebrows, a raw suggestive laugh and teeth lined with gold. The houses were tiny. But he was more interested in telling us about his European friend. He sent his younger sister upstairs to the bedroom to collect some photographs, which he proudly showed us. They were of a man with other men driving a red car in front of a building vaguely and unconvincingly identified as a restaurant. The European on the photograph was an importer of tropical fruit said the man with his gold teeth; it was obvious he was very proud of his friendship. He cherished the photograph. We were standing in the very narrow passage within the ciudadela that lead along the string of tiny houses. The women around him seemed to accept his domination of the conversation as a matter of course. At the end of the passage was a tiny concrete pen holding two large pink pigs. Next to it was the communal bathroom for the whole street.

We went to eat Chinese again. It was great fun. After we finished we all took a bicycle taxi (4 in all) and had a race back to the hotel. Laughed till we split. Good bunch of students.