Havana I

Diary, 19th October 1998:

Our first afternoon in Havana. What an extraordinary city. We arrived in the newly built airport, finished some six months ago: all space-frames and welded steel in red, white and grey. Having our passports checked was an interesting experience. Coming from the aeroplane you are led through a corridor overlooking the runway and lame looking aeroplanes rotting on their patch. From there you are funnelled into a large and merciless salle des pas perdus, divided into long segments by long lines of waiting people. Each row waits in front of a window and a door. Through the window we can see the profile of a custom’s officer, dressed in an emerald green uniform. Other men and women in military uniform are dotted about the waiting hall. They talk with each other purposefully, there is no sign of small talk. The custom's officer in the cubicle behind the window, faces another window at right angles to the one we can see him through. Behind this window stands the person who has just gone through the door and is at that moment under intense examination. The short corridor he or she stands in is narrow and of the same length as the custom officer's cubicle. It has two doors one leading back to the waiting area, the other to Cuba’s interior which begins with a fully modernised luggage collection area. When I went into the cubicle I faced the lady checking my passport. Behind me, against the ceiling was a mirror into which the lady looked at regular intervals. I got through without any delay and a simple almost unnoticeable green stamp in my passport.

When we emerged from the luggage collection hall, having had ourselves courteously checked by one of the many men in emerald green, we were met by two professors from the school of architecture. We drove by bus to the Hotel Vedado, a wonderful drive along a wide and very straight road lined with curious concrete buildings, many of them daring if not altogether hopeful experiments in housing form. There were circular single-storey minimum-existenz houses as well as a vast laboratory in glass and concrete. It was an optimistic architecture, full of the future and full of disappointment, in the past and ultimately, in itself. All of it was slowly decaying. There was a huge sports complex in concrete, daringly enormous Corbusian Housing Estates, housing a dignified but palpable and sometimes overwhelming poverty.

The Hotel Vedado could not put us up. After a lot of toing and froing and the helpful intervention of the Dean of the School of Architecture, Mr Bancroft, whose ancestors came from Jamaica, a fact to which his surname still attested, we were put up in a four star hotel for the same price. We walked up and down between hotels and shuttled back and forth in the dean’s Lada jeep which was driven by a surly jet-black chauffeur who showed contempt for everything and drove with a dramatized reluctance. Talking to Mr Bancroft while waiting at various desks, manned by helpful reception ladies, to have our hotel arrangements finalised, it soon became clear how immensely proud he was of his city and his country. And this despite the fact he had to invest most of his time looking for ways to stay afloat. Somehow this proud lack of funds rhymed well with the once magnificent and now paintless buildings of which Havana is full.

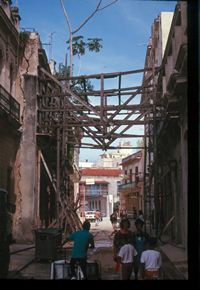

Dilapidation in Havana has reached the level of the mythological, so much sheer exhaustion, some of it collapsed under its own weight, other buildings standing like Lazarus. At the same time it is a very different form of dilapidation than that affecting Kingston. The dilapidation of Havana is not from passive neglect and an apparent carelessness, it is far more conscious than that. It is a careful neglect, a studied neglect, a purposeful one. Firstly, the neglect is conscious; it was part of a political plan to redirect resources from Havana to the countryside. And when resources dried up, that was that. Secondly there is the studious nature of the neglect, which is visible in the care which is taken to stretch the useful life of the buildings and the cars so far beyond what could be reasonably asked of anything. Cubans understand their cars and their built fabric from that point of view and prioritise accordingly. This is also manifest in the way that objects made for consumption are not consumed but endlessly preserved, embalmed. Consumption in Havana does not obey the same laws as it does elsewhere.

In the evening we went for a walk. It is a dark city, few lights and few noises. The televisions echo through the bare rooms with their high ceilings, making the walls come alive with the vague reflection of moving colours. The hollow noises carry into the streets. Life at night, indoor life, is not kept a secret, one can look into the open doors to see… men watching television, mostly. The interiors are sparsely decorated with pictures of lovely ladies and Christ, the great comforters, a few old books, artificial flowers, fussy glass objects, pictures of grandparents and more pictures of Jesus.

Everyone except for the men watching telly is out on the streets, talking. Young couples clasp each other casually, with only attention for each other. Others look around and are aware of their surroundings, people are polite and allow everyone their space. It is a different way of being in public space to what I am used to in the streets of Kingston. The streets themselves are different. Here they are properly urban in a romantic sense of that word: the pavements are narrow, the buildings high, the sky reduced to narrow bands, rivers in the sky. In Kingston the sky is broad at night in the street, the buildings are generally low, except perhaps in Knutsford Boulevard. The noises are different. Kingston is characterised by the highly localised but intense rhythmic beat of the base coming from large speaker walls lining the pavement. In Havana it is different: more couples, more mystery, less excitement and above all more tired.

The cars are marvellous as are the motorcycles with their side-spans. Old bicycles negotiate their way through the traffic with girls on the back holding on to the men doing the work. In Jamaica these men drive high-powered motorbikes of the latest make; the delicious bottoms of the girls are thrust into the air as if to receive the power from the engine. It is a direct sexual experience, in your face, without the complications and tortuous demands of sensuality. In Havana the girls I have seen so far on the back of bicycles and motorbikes, which are not many, do not clasp and thrust with such explicit clarity. We walked up the steps of the university but we were not allowed very far. Somewhere within the grand staircase a window revealed itself and a man behind it shooed us away. The university is a grand early 20th century Greek revival thing; the staircase is “very” baroque and conscious of its single-minded purpose to display and symbolize, to express and be the metaphor for the ascent of national truth, the Cuban Parnassus. The staircase is terraced to allow secondary staircases to branch off towards a regiment of buildings standing to attention along the route which ends with the main university building, heavily pedimented and endowed with enormous columns: a Greek revival extravaganza. The buildings along the staircase are carefully placed and sized to second this impressive centrepiece. The lower buildings are strongly articulated, as if they form an overture to the main event while the upper buildings are shallower, flatter to hold back for the enormous presence of colonnade and pediment, which they frame as well as they can. Turning around one becomes the focus of two long straight streets meeting just below the staircase and which descend into the old city. A beautiful bit of urban theatre.

Just near our hotel, which is called Hotel Capri by the way, there is a huge apartment block called the Focsa Building, by Jorgé Luis Sert. It counts 30 floors, folded down the centre like an open book: two enormous box-frame slabs joined in the middle at an oblique angle with a third, shorter arm protruding at the back. The building takes up a whole block in the grid. The two main arms are set at 120 degrees to each other, like the pages of a book or perhaps like arms reaching out to embrace the old city from its place on the summit of the old stone quarry, one of the last stretches of the Havana coast to be developed before the revolution. The Focsa is monstrous, truly awesome. Some 600 apartments stacked on top of each other: a serial-killer apartment-block. All of them face East and the rising sun and turn their backs to the West and the setting sun. There are no windows to the north or the south. This is interesting as it is usual, and good sense, to order your high-rise apartment blocks east-west when near the equator, so that the larger surfaces catch less sun, or that at least the southern side can be kept blind or be shaded by brise-soleils. Many balconies have been claimed over the years as interior space and windowed up as extra rooms. The square holes below the other windows are boarded up, these holes used to contain air-conditioning units. The Focsa was a building for the future as envisioned in 1959, just before the revolution. It presents a political modernism which had thrown its functional thinking to the wind and sacrificed practical priorities to making of grand symbolic gestures. Air-conditioning had arrived to stay and would help to create a new world of temperate comfort.…. That was then. now one looks at the browning concrete, the lumps that have fallen down, the missing panes of glass and the squalor of it and one thinks of the amount of shit that has to travel the pipes each day.

I have American television in my room. CNN and all sorts of other channels.