Grid, The

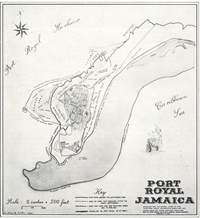

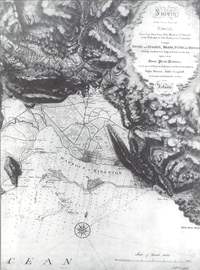

Kingston is a city that was, quite literally born from calamity. It was heir to the robust and wild city of Port Royal, the hub of British maritime life in the Caribbean, situated at the end of a long peninsular arm embracing the enormous natural harbour on the southern coast of the island. Port Royal was garishly coloured by the licence that the more aggressive side of the entrepreneurial spirit likes to nourish itself with. The law was distant and difficult to administer. The stories of that wild spirit are plentiful, of Sir Henry Morgan, for example, whose piracy was institutionalised and used as a political tool by the English against their Spanish rivals.

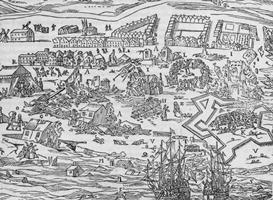

In 1692 the city of Port Royal was swallowed by the sea because of an earthquake. It was considered a deserved if apocalyptic act of retribution. At the time the story went global with a description of the event translated into every major Euroopean language. A new era in the history of Jamaica was about to begin, one where the primary focus was not the sea and its fluid tendency to erase the lines of order imposed upon it: but the land, agriculture, with its tendency to retain them and use them to forge a new reality. Within this era of consolidation, what remained of Port Royal reverted to a more specialised function, a small marine base, a function it has kept to this day.

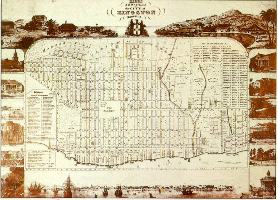

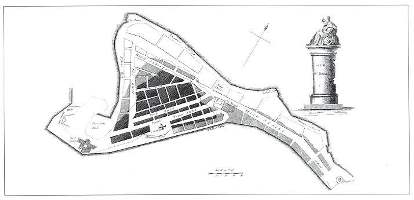

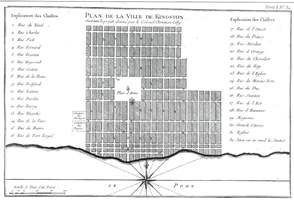

The parish of St. Andrews had already been divided up among the soldiers who had helped expel the Spanish in Modyford‘s expedition to Spanish Town. Colonel Barry, one of them had sold his lands to Sir William Beeston who had arrived in Kingston five years after the conquest of Jamaica in 1660: 200 acres for £ 1,000. That land was neatly divided by John Goffe into a nicely modulated grid, the mother of a colonial aesthetics of manifest order.

The west of the slightly elongated parallelogram was bound by West Street, the east by East Street, the south by the memory and view of Kingston’s predecessor: Port Royal Street of which it gave a view, and to the North is was bounded by North Street. That is the kind of grid that is neat and pleasing when seen from above, filled with apparent self-evidence and reminiscent of the neat orthogonal disposition of the Egyptian pyramids and subject to the same geographical geometry. If the Nile goes more or less exactly from the south to the north, Jamaica, as an island is elongated exactly according to the east west axis. That satisfaction in geometrical clarity is echoed in the plan and continues in its further division directly inspired on the military aesthetics of the Roman castrum, with its cardo and decamanus and, if less directly on the more sophisticated morphology of Hippodamus’ plan of Miletus.

The main street, King Street, slightly wider than the others, dissected the parallelogram, like the cardo from south to north, furnishing the economic interface between land and sea. It passes through a square at dead centre, a military camp called The Parade and is intersected at that point at right-angels by an aesthetically and symbolically motivated East-West street, which, to give expression to the machinations of dynastic perpetuity, was called Queen street: the royalist credentials of the city Kingston were engraved through its heart, even though the conquest of Jamaica had initially been inspired by Cromwells’ Grand Design. The subsidiary streets memorised early notables including Beeston himself, Beckford, whose descendants we shall come across a century later. Orange Street, parallel to King Street deserves a special mention, because it has a connection to the Dutch through the person of King William of Orange who was king of England at the time that Kingston was being conceived and built. He being the King of the erect and vertical King Street penetrating through the parade, would make Mary the the Queen of the supine Queen Street. The mind boggles. They had no children and the British crown passed after a brief period in the Hands of Mary's sister Anne to the Germans of Brunswick-Hannover.

In the middle of the square, which was a near exact square, almost true to its name, was a cistern, water being the primary support of urban possibility. What is particularly subtle about the plan and has a similarly symbolical and ideological significance is the way that Kingston Parish Church was the only building allowed to penetrate the square, disrupting its geometry in an act of righteous religious assertion, an act prophetic after the fact, as religion is one of the mainstays of Jamaican life, an extraordinary force penetrating to the very heart of its existence.

The rest of the parcels of land were carefully measured out, giving expression to anticipated value of localities: two rows of smaller parcels near the harbour, then two rows of slightly longer parallelograms, succeeded by a single row of attenuated plots which border the parade to the south. The stroke of blocks at the height of the Parade , perhaps because of the need of its symbolic dissection by Queen Street, were cut in half giving double square plots.

Underneath the rich language of symbolism and affiliation lay a cruder game of land speculation. Sir William Beeston, already wealthy, became exceedingly rich and played the games of extortion to perfection when he returned to the island in 1693 from a sojourn in England. This time he was the Island's Governour. He immediately declared the initial sale of land illegal, repossessed the 809 lots and then resold them for £ 5 pounds each, a near 500% increase on the initial price, all the while ensured of a future security by the fact he already owned 330 acres of land surrounding the city.[1]

A contemporary Illustration of the Port Royal Earthquake, (From: Clifton Black, History of Jamaica, p 49)

[1] Anthony Johnson, Kingston, Portrait of a City, Kingston 1993, p. 48. On the grid of Kingston see also Dr. Wilma Bailey and P. Stanigar