Great-house, The vocabulary of

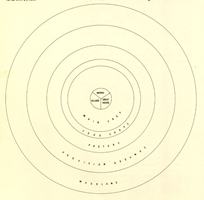

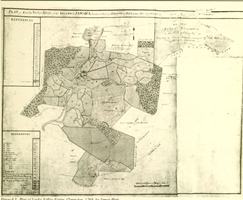

The land is surveyed. It is ordered concentrically, the works, where the crop is processed, takes centre stage. The slaves are tucked away in small villages, preferably out of sight and left to overseers. They like being out of sight. The slaves are given land to cultivate in their spare time at the edges of the estate. The best land is used to grow the main crop, the rest is used to graze the animals. The great-house has a luxuriant relationship to the estate and its landscape; it is given the most beautiful place. This is where the plantation owner or his manager lives. At the same time it must not neglect its duties and so it is placed atop of a hill, or against a slop, to give it a good view of the works. The great-house, in beautifully crafted detailing and its manifest comfort expresses ownership while demanding a lordship of the eye; it is very visible and all-seeing simultaneously. The fortunes made are exported to England in the form of the crop. Owners are absentee landlords represented by managers. After emancipation the geometry begins to change, the industry becomes more fully mechanised. No longer is it just men completing the rigid circles of production but they are joined by steam and later electricity. (Higman)