Functionalism

Function, purpose, use: to function, verb. To function means to work with regard to some purpose. A purpose is the answer to the question: “what can {a} be used for?” Actually it is slightly different. A purpose is the answer to the question: “what can {a} be used well for?” For something to function it can be said to work. How does something work? How does something function well? The answer to this would be: By performing a function in such a way that the person making use of the thing under discussion, says or thinks to himself: “this is functioning well”. Does there always have to be a person thinking or saying something? Perhaps not. Usually when something is functioning well people are happy to let it do its thing. But that at least is a silent judgment of the same order. To allow something to get on with what it does well, is to trust it in that capacity and to be happy about it. What is capable of functioning? When we look at our use of language, our best guide, we come across sentences as: “this hat will do”, which means that the hat can function to keep the head covered or that the hat might be used effectively as an oven glove, or whatever. Alternatively one comes across sentences such as: “she’s done a marvellous job” which means that the lady we are talking about functions well in whatever it is that her job entailed. When we say: this law, or building, or way of doing things works well, we all know what we mean: they work and we are happy about it. So the word function appears to cover pretty well everything where some kind of work is at issue. The work might involve communication which means that the thing functioning functions well because the message it carries is well received and leads to appropriate behaviour. A sign might function when it tells people to be careful when crossing the road, The work might also involve something more active, something more machine like, in such a case the work might involve movement or the application of some force.

So what then is functionalism? All isms are doctrines of some kind. That is, they are theories about how to do something well according to some idea we have about the world. The functionalists felt that the form of a building should be a response to a demand, that we should derive form from an understanding of the program, or rather the purpose of the building, what it is for. By determining the relationship between form and function, namely that form should follow function is not without problems. If form follows function then that implies that one should study the purpose of a building and on the basis of an analysis how that purpose can best be fulfilled derive the appropriate forms. That is a very compelling way to think about design. It reduces the design task to a puzzle: you get your challenge and you solve the problem. That would be ok, except that the relationship between form and function is more interesting than that. Forms suggest all sort of uses and when we want to do something we look for the appropriate form that fits what it is we want to do. If we want to dry our hands we look for a towel. If we want polish our shoes we will not grab at the towel but look for a cloth that is better suited to that particular purpose. In other words the relationship between form and function is predicated on the relationship between form and the behaviour of that form, or the behaviour that a particular form allows. The relationship between form and function can be seen as a solvable problem, but that would only be useful in acute situations where you need something quickly. When you have more time, you are given the time to play and explore, to tease and consider. In fact the relationship between form and function is indeterminate. New forms can accommodate old functions but can also suggest new ones and so forth.

What the moderns did is that they made the age-old function-form relationship restrictive. They decided that it should only apply to relationship they approved of. In fact they made functionalism into a catechism and a form of ornament or atmosphere creation. There is nothing wrong with ornament. On the contrary, the function of ornament is to differentiate space, to make something special relative to something else. At the same time I cannot help feeling slightly confused at a movement that despises ornament, wants to do away with it, only to replace the ornament they did not like with a way of dealing with surfaces and space that they did like, by designing another kind of ornament, an abstract ornament, which can be very beautiful, but functions in exactly the same way as ornament does. I would have found it more honest if they had said: we don’t like that kind of ornament and so we are going to design a better kind of ornament. That is what they did, but not what they said. What they said was that they could do without ornament and that they wanted to concentrate purely on function. That was, quite simply, not true.

In fact their rather ornamental functionalism, or functionalism of atmosphere, in which not so much the form as the surfaces making up a space and the sphere constituted their response to the way an activity should be dressed by the space it is conducted in, derives from a way of approaching design that is as old as civilisation itself: the appropriate adjustment of means to ends, the creating of appropriate spheres and settings. That functionalism we find everywhere.

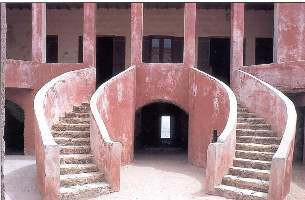

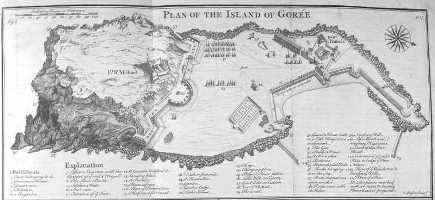

The functionalism they talked about believing in is more akin to the architecture of moments in our history no one in hteir right mind could surely be proud of. The ships coming from England, France, Spain, Portugal, and The Netherlands would stop in various places in West Africa, where the slaves were stored in quasi-military forts such as at the Island of Goree just off the coast in Senegal. The name Goree is derived from a peninsula in the province of Zeeland, The Netherlands which carries the same name. The island was successively in Portuguese, Dutch and French hands. It saw the shipment of some 2 million slaves to the Americas. It is a sombre place, not unlike Alcatraz and indeed now functions as both a place of pilgrimage and as a prison. The purpose of the fort was security and containment. The form of the building had to accommodate the interface of the slave trade between the mainland in Africa and the Ships.

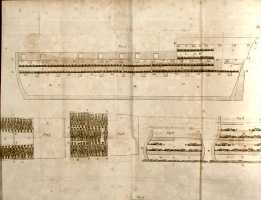

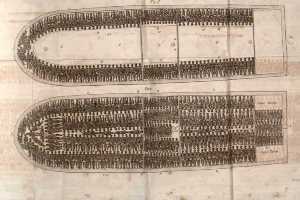

The slaves, being regarded as objects needed only undifferentiated containment. Undifferentiated? not quite. Undifferentiated in terms of family structure and kinship, tribal attachments etc. But there was in fact a very stringent differentiation. The slaves were sorted as products and stored accordingly: women, old and young, children, men. Because of the inconvenience of their being alive and the concommittant consumer advantage that their being alive obviously brought, they were chained. It was all part of the packaging process. That packaging process took on a functionalist aesthetic in the ships. As the harrowing images recall, a brutal functionalism determined the way the slaves were “housed”. The leading design idea was to maximise the cargo-volume while minimising necessary maintenance to ensure the delivery of an adequately fresh product. The diagrams produced by the anti-slavery movement dramatize this formal functionalism, this “efficiency.” This functionalism persisted and after arrival in the target country. The way the slaves were marketed emphasized their status as marketable objects, the way they were put to use on the estates marks a proto-industrialism in that they became machines for production.

This was in fact the functionalism of modernity; it was a restrictive efficient functionalism, an aesthetics of form following function. This is not a bad aesthetics in itself. It can and does often produce great designs and it can be abused to mistreat people or the environment. Everything is subject to abuse, also a great aesthetic principle. So my fight, if fight it is, is not with the aesthetics of functionalism as such. My fight is with the restrictive interpretation of functionalism, the idea that, for instance, a rococo scroll cannot have a function which it could be said to perform well, that a Mexican church altar cannot be said to perform or function well and could thus be seen as a case of functionalist design. That is wrong, just as it is wrong to use people against their will. We should not ask ourselves whether something has a function. We should assume it has an infinite number of possible functions all of which are related to its form. Design should be concerned with the relationship between form and function. It should let these aspects of behaviour negotiate a response to every challenge. But apart from looking at function we should also look at justification. A design and every design decision needs to be justified. To treat people as objects, as commodities, as machines can only be justified if you use them well. Good use requires people to give their virtues, their skills and knowledge freely to whatever purpose they decide to devote their energies. To treat things as objects, commodities and machines is free. Having said that even a machine takes a stand when it is used badly, when it is not maintained and cared for, it stops working.