Cafe van Moll, Present and taking part in the discussion: Jan, Jos, Jacob, Mark, Marta, Peter, Stephen, Teije and Wouter.

This is the story of the meeting:

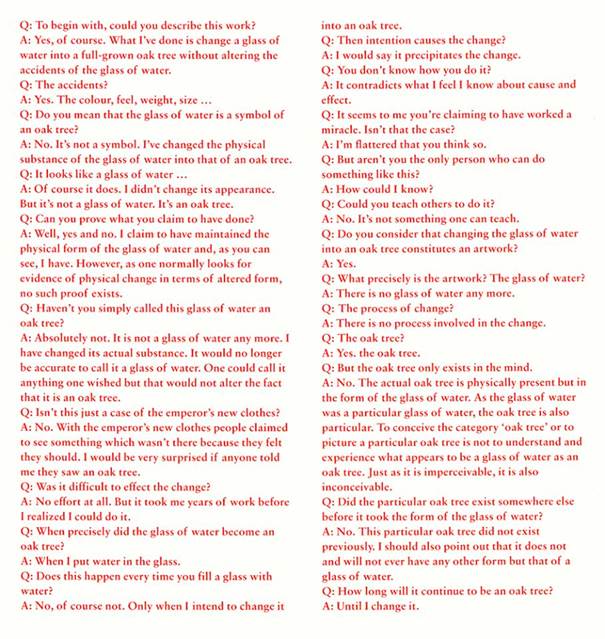

The theme was brought in by Jacob who wanted to talk about a work of art he had seen in the Tate Britain by Michael Craig-Martin. It was called “An Oak Tree” and was made in 1973. Below you will see a picture of it.

It is difficult to decide what exactly constitutes the work of art. Is it the printed conversation, between “Q:” and “A:” (bottom left), or is it the oak tree in the form of the glass of water sat upon a bathroom shelf suspended on the museum wall? (top) Should we include the information (bottom right) Or is it perhaps all that and more? Is it also the process of thought you begin as you wonder about this strange and frustrating work of art and the circular conversations you have with others about it?

The conversation accompanying the oak tree in the form of a glass of water was read out by Stephen (Q) and Jan (A). It goes like this:

Logic

The problem with this work of art is that the conversation accompanying it is logically sound. This may sound strange but that is nevertheless what the problem is. You cannot fault “A:’s” arguments about this act of transubstantiation. When “A:” says that it took years for him to realize he could change a glass of water into an oak tree, one can certainly believe that it took years to craft the logic of this story and make it work so smoothly. “A:” like a good chess player, makes not a single mistake; he makes no claims he cannot logically make; he says nothing that is clearly untrue or that can be disproved by anything other than the force of habit and convention or what we might trivially call common sense. He does not claim to be a magician. If he was a magician, the glass of water would take the form of an oak tree but it doesn’t. It looks like a glass of water and there is nothing to distinguish it from a glass of water. Nor does “A:” claim there to be anything to distinguish this oak tree from a glass of water. Magicians are good at turning princes into frogs and sailors into pigs, but “A:” is no magician. So, to puncture his armour of logic we might apply the American general’s sound advice: If it looks like a duck, flies like a duck and sounds like a duck then…. it probably is a duck. There, we have dismissed this bogus work of art. Except that we haven’t. Using the general’s argument is weak and it will get us into trouble. Some things that look like ducks are soldiers in camouflage.

No, “A:’s” logic is impeccable and all have to fight it is our own narrow-minded, blunderingly dismissive common sense. Surely that is not good enough. The problem of this work of art is not a problem of logic; the problem is precisely that there is no problem with its logic.

Semantics and representation

Nor is it a problem that confines itself to mere semantics. If it were a problem of semantics we would ask questions like the one “Q:” asked: “Do you mean the glass of water is a symbol of the oak tree?” “A:” responds that it isn’t. The glass of water, “A:” claims, is an oak tree. It does not represent an oak tree, nor is it a metaphor for an oak tree, it is one. At the same time the work of art very clearly shows us a glass of water. This is not the same problem as Magritte’s ceci n’est pas une pipe, or indeed his investigation into names and their relationship to things: Un objet ne tient pas tellement à son nom qu’on ne puisse lui en trouver un autre qui lui convienne mieux. The name ‘oak tree’ does not suit the object presented, which looks very much like a glass of water. Name-swapping rather confuses things. An oak tree is an oak tree and a glass of water is a glass of water and the names suit their objects just fine thank you very much. The problem is that this particular oak tree has the form and appearance of a glass of water and even shows the behaviour that is common to glasses of water. But it does not particularly suit the oak tree to have that form and appearance.

Epistemology

Nor is it really an epistemological problem; that is a problem concerning the way we arrive at knowledge about the world around us. It is a bit of an epistemological problem of course. After all we see something, but it turns out not to be the thing we see. We see a glass of water but it is an oak tree. How can we acquire knowledge of the quiddity, the oak-tree-ness of the oak tree if it looks like a glass of water? Answer: we can’t. “A:” does not claim you can see an oak tree; he claims, quite correctly, that you see a glass of water which, however unverifiable, is in fact an oak tree. The seeing of a glass of water we can happily verify; its being an oak tree baffles us and we want to contradict it but can’t, at least not on epistemological grounds. After all “A:” has stated quite clearly that we are not fooling ourselves when we see what we think is a glass of water but is in fact an Oak tree. The oak tree is simply cognitively hidden as a recognisable image. So that might be something of an epistemological challenge but it is no more than that. It is after all quite possible for things to be one thing and to present themselves as something else. We call such epistemological challenges ‘camouflage’ or ‘lying’, or ‘masking’ or ‘presenting yourself in virtual space’ or whatever.

Psychology

There is a clear psychological problem in the form of a psychodislepticum. We are confronted with something rather mundane: a glass of water on a bathroom shelf, and are then twice taken out of our comfort zone. The first eviction from that comfort zone we have come to expect. A glass of water on a bathroom shelf in a museum means: modern art, beware! We have come to expect modern art to want to confuse, anger and frustrate us. That is its task, its charm, part of the game. Unfortunately we are getting worryingly used to it. Nobody looks twice at a urinal being a work of art. We have lost the boundaries that modern art so happily exploited in the past. Mind you there are still lots of people who would say, either at the urinal or at the glass of water: “that is not a work of art, that is just rubbish!” So in a sense normal people (whatever they are) also indulge in transubstantiation. Duchamp changed a urinal into a work of art while keeping the appearance of a urinal and his detractors transform it from a work of art into a piece of rubbish. That is the secret of being-as-finding. Things are what they are when we think something about them, when we find them to be this or that. We might ask ourselves whether this is substantively different to changing a glass of water into an oak tree. The moment we stop chuckling, smirking or laughing and think about the problem seriously we soon find ourselves having to acknowledge that “A:” cannot easily be refuted without getting ourselves into trouble. The transubstantiation of the glass of water into an oak tree without losing any of its physical characteristics becomes our personal psychological problem. If we are not careful we shall become subject to explorative obsession and explanatory neurosis!

Madness

As we descend into madness we cannot call “A:” mad without paying a very high price. Madness manifests itself in people who say and do things that other people believe to be ridiculous. Applying the label of madness is a technique for keeping these people on the outside of any community. That might be a very useful technique. I am not sure. But if we call “A:” mad we’d be calling someone mad who does not transgress the boundaries of logic. We have to be careful before going there; a horrible paradox appears when we do. We would be saying: “You are being perfectly logical, but we shall call you mad anyway.” In that way we would consign ourselves to madness in the sense that we would be contradicting the very rules of logic we set such store by. After all, “A:” is being logical, and in pronouncing him mad we would be illogical. Or has madness nothing to do with logic? Is madness purely a social thing? If so, would we want to be part of a society that calls its logical creatures mad?

Ontology

The oak tree in the shape of the glass of water tells us something about the very nature of metaphysics. What did the wine look like that Christ changed his water into? It must have tasted like wine and worked its magic like wine and I imagine it must have looked like wine too. Otherwise people would have been suspicious. Christ was something of a magician-miracle worker. “A:” isn’t; he is just an ordinary man quietly and imperceptibly transubstantiating a glass of water into an oak tree. That makes it into a very frustrating work of art because it cannot even claim miracle status. The only way we can keep our sanity is by saying “well, we’ll just take your word for it.” Other than that we are powerless.

Giving in to the trivially true

And so we run our head up against a brick wall. “Sure,” we say, “the glass of water we see is an oak tree. You have done your trick. But so what? It makes no difference whatsoever to our use of the oak tree that is shaped like a glass of water and behaves like one. We will still be using that glass of water to nourish us. So if it is an oak tree that fact will make no difference, we’ll go along with you, in order to shut you up. We ourselves have already given a place in our mind for the concept oak tree, but we can cope with a small gorge in our linguistic landscape, we’ll just humour you and drink the glass when we a thirsty.”

Authority

But that too is not quite satisfying. Why should we give into him? Let’s investigate the nature of his authority. Why do we see it as giving in when we call the glass of water an oak tree? Why should the glass of water being a glass of water have primacy over our expectations? How did we come by the fact that it was a glass of water in the first place? It was mum and dad who taught us to call things like that thing sitting on the shelf a glass of water. They taught us what to do with it and encouraged us to use it well; which meant respecting a whole list of rules about what you can and cannot do with a glass of water. All that has been extremely useful but what makes their authority greater than “A:’s”? Answer: I don’t know. Perhaps it does come down to semantics after all. Perhaps we should get used to drinking oak trees and lying on the grass and looking up at glasses of water during the summer months? Does it come down to that, a kind of symmetry in naming things? Mum names it this and “A:” names it that. We are left to choose whom to follow; it is our existential choice. It is only a glass of water because our culture calls things like that a glass of water. It helps to have common names in order to communicate about things.

Does it then come down to naming things after all? Is it merely a problem of rigid designators clashing? No, this is clearly not what “A:” says. It is and oak tree and he gives us no hint that oak trees are for drinking and glasses of water are for sitting under during the summer months. He is not asking us to swap names. Nevertheless, whoever has been confronted with the work of art and has given it serious consideration, will have added a rigid designator to their conception of oak trees and glasses of water. So that whenever such a person sees either he will be contaminated by his obsession with this work of art. But that will only be a temporary problem; his obsession will fade over time.

Trivial being

It is truly a metaphysical problem. The thing looks like a glass of water but is an oak tree even though it has the appearance of a glass of water and even though it works like a glass of water. And the oak tree it is can certainly not escape being used as a glass of water. This gives us a way out: its being an oak tree is of no significance whatsoever. It’s being an oak tree is merely trivial. It has no consequences, no effect. Move on. Next!

If that is true, then why are we here talking about it? Why are we using this work of art as a thing to talk about? We do so because it reveals to us something of the problem of being. Being, is being-in-relation-to. What things are in themselves is inaccessible to us. All we have access to is what things are to us: being-as-finding. Things are what we know or think about them. What is a glass of water to us? What do we really know about things? What do we know about glasses of water? Let’s put it this way. When one of us says “I know Wouter”, then what does such a sentence mean? I don’t really know Wouter. I have met him a number of times, became happily drunk with him and enjoyed his company. I know he can cook well. I know something of his appearance and the way he usually behaves in public space. But that is all. What is this thing we call Wouter? He is in fact mostly unknown to me, mostly unknowable even to himself. The set of relationships I entertain when saying “I Know Wouter” is really very tenuous and fragile, small in number and says very little about him, just enough to be useful in conversation. Were we to talk of Wouter more often we would gradually build up a fuller picture; but that takes time. The same is true when I say “I know what a glass of water is…” I may know how for instance glasses are made; I may know the symbols we use to represent water in chemistry class. I may have heard fascinating things about water’s properties, I may be grateful for its soothing and thirst-quenching effect when it enters my body through my mouth. Does all this constitute knowing? I suppose it must. At the same time it seems experientially rather poor. This is why it flies in the face of everything I believe I know when “A:” calls what I see as a glass of water, an oak tree and I cannot even contradict him with anything more than a frustrated “no it isn’t. I know oak trees and they do not look like that or behave like that!” We are back at the general’s argument.

So what would it mean for this thing that looks like a glass of water to in fact be an oak tree? It means nothing much at all. I can still use it as a glass of water. So [being something] means [me knowing how to use this thing because I know how it behaves and what effects it is capable of in my environment.] I know what something is when I build a set of more or less coherent relations with it. I cash this knowledge in when I use it for whatever purpose I can. I can thus be happy that it is an oak tree and use not only its appearance but even its properties in the way I would a glass of water. It has stopped mattering whether it is a glass of water or an oak tree. I have been reduced to silence about it and just get on with my life.

Except that I can’t. Something is still bugging me. Let’s try another approach. What is the difference between the statement: “this is a glass of water” when pointing at a glass of water and the statement “this is an oak tree” when pointing at something that looks like a glass of water? They are both simple predicative statements. I command the one thing to be an entity labelled by a noun and I command the other thing to be an entity labelled by a noun. Nouns name entities. Entities are things we have commanded to be entities. The only difference between the two statements is that the rigid designator “glass of water” feels right when the statement fits with what is being pointed at and in the other statement this fit is missing. That is the psychological problem coming round again. But as I cannot find a mistake in “A:’s” logic, I am brought into a state of confusion and all I can do is say “Well, I’ll take your word for it.”

Ok then, another tack. What is the difference between the statement “this is an oak tree,” when pointing at a glass of water and the statement “this is beautiful” when pointing at that same glass of water? Well, the first we have already covered. We name an entity an oak tree which does not appear to fit with our expectation of what oak trees look like. And in the second statement we qualify this entity by calling it beautiful. The word beautiful does not work like a name, it works like an adjective. We cannot say: “this is a beautiful” it makes no sense. However we can say “this is a beauty”. But even then we use the noun beauty in an adjectival way. But if you think we have thereby explained the difference between the two statements, then think again. In essence we have still commanded something to be something. And the interesting thing is that this something is this quality as it relates to me. You might not find it beautiful. And this gets us to a knotty problem because it shows that something can be something and at the same time not be that same thing! Moreover it is possible for something to be something in a different medium. Whose presence is present on Mark’s Facebook page? Can we say: “Here is Mark!” when we get to that page? Whether we can or not, we certainly do. At the same time we know what we mean by that; we mean: we understand the nature of Mark’s presence on Facebook, it is a virtual presence that unfolds itself when we look at the pictures he has posted, read the comments he has left behind, receive the response we expect when we leave him a message, etc. In fact that is really all I can say about “knowing Wouter..” I know some stuff about him and can identify him in space and talk to him. So the difference between Wouter next to me and Mark on Facebook is a difference that is not easy to describe. We call the one real and the other virtual but if Wouter were a perfect hologram, able to entertain me in conversation I would be perfectly happy to believe that it is him in the flesh. Everything would fit and I would be happily unaware of his being different. The oak tree does not fit as a glass of water, but I just have to accept the possibility that it is an oak tree, just as I may accept that the hologram that is indistinguishable from Wouter is in fact him. When I call something beautiful I too am naming it, accept that I when I name it beautiful it is also an entity with a different name. But we have just admitted that this is true of everything we name. When I name Wouter, Wouter, I name something about which I know very little. I am sure Wouter is much more than what I know of him. On this basis I give him many more names: man, architect, cellist etc. The label beautiful qualifies an object but I could also use any noun as an adjective. We could say: “That is a very glass-of-watery kind of oak tree!” So there is no real difference between the statements: “this is a glass of water”, “this is an oak tree” and “this is beautiful” except that we have learnt to differentiate them into various expectations.

And what actually is the difference between an oak tree and a glass of water? There are lots of course. We do not even need to list them. But what is interesting is that they become less and less important as we move down the scale to the level of protons, ions and bosons or indeed if we move up the scale to the level of galaxies and the universe. At the atomic level the difference is combinatorial. At the scale of the universe it is squashed into insignificance.

One of the most worrying problems in philosophy is possibility of solipsism, the belief that you are the only person really alive, and that all the rest have been put there to give your life a context. It is a foolish belief, and truly damaging should you take it seriously. However it cannot be disproved. It is always possible to doubt the nature of your environment even if you cannot doubt yourself thinking about it and thus you being yourself. What being you means, is extremely problematic. But we won’t go into that now. Similar to solipsism, Michael Craig Martin’s work is fascinating because it cannot be refuted. All you can do is make an irrational decision. You tell yourself solipsism is wrong and that Michael Craig Martin is talking rubbish. In other words you are forced to be a little mad in order to avoid a greater madness. But in fact I am on the point of not just giving in, but feeling completely happy at this glass of water being in fact an oak tree. It is making the world a more interesting place; it is enriching my experience of things. I am enjoying myself.

After this we felt we had exhausted the topic. We paid for our beer and left. Oh by the way, this story is not the story of the meeting. The meeting had all these ingredients but not quite in this order or with this level of detail.